By Maesy Angelina

By Maesy Angelina The previous posts in the Beyond the Digital series have discussed the distinct ways in which young people today are thinking about their activism. The fourth post elaborates further on how this is translated into practice by sharing the experience of a Blank Noise street intervention: Y ARE U LOOKING AT ME?

In a previous post, I have shared how Blank Noise is unique in articulating its issue: it does not offer a strict definition of eve teasing nor does it propose a specific solution. In another, I shared that Blank Noise’s main goal may seem to be to raise public’s awareness on eve teasing, but it is actually secondary to its less obvious objective to provide a space where people can become empowered through its personal experiences in the collective. The main strategy employed to achieve these goals is to create a public dialogue through artistic and playful means, both at the physical and virtual spheres. The interventions attracted media attention and volunteers, but the main impacts are internal: people are able to personalize the meaning of their involvement in Blank Noise and undergo individual transformations.

This post will flesh out how these elements are actually translated in Blank Noise’s interventions. It is difficult to pick one example Blank Noise a wide variety of interventions as it evolves through the seven years of its existence. It started in 2003 as Jasmeen Patheja’s final project when she was a student in the Sristhi School of Art and Design in Bangalore. At this first phase, Blank Noise consisted of nine people and dealt with victimhood through a series of workshops that became the basis for small art interventions. As s many other activist groups before them, Blank Noise took the initiatives to the physical public sphere: the streets, bus stands, public transportations, parks – anywhere outside the home. Blank Noise decided to move forward and try to engage the wider public in 2005 and engage more volunteers than the initial group of nine. Despite being more well-known lately for its virtual presence, the collective only started its first online intervention in 2006 and street events remainan integral part of its being. Given this history, and also because this is the one most often brought up in my conversations with the Blank Noise people, I choose to share the ‘Y ARE U LOOKING AT ME’ street intervention experience.

The experience starts with a post in the Blank Noise main blog and e-group, announcing a date and time for the next street intervention. The announcement is accompanied by an invitation for anyone who reads it to participate and come to a designated place (such as the popular café Coffee Day or the famous Cubbon Park in Bangalore) for a preparation meeting and also the actual intervention (sometimes immediately afterwards). When the time comes to for the meeting, the faces that appeared are varied. Some are regular faces in Blank Noise meetings and interventions: perhaps Jasmeen, others who have been coordinating interventions, or regular volunteers. Some faces are new: people who read the announcements online, heard it through word of mouth, or those who were around and curious about the gathering. The number could range from three to more than 100. Most who came were women although there were also men.

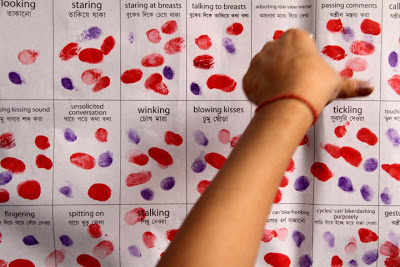

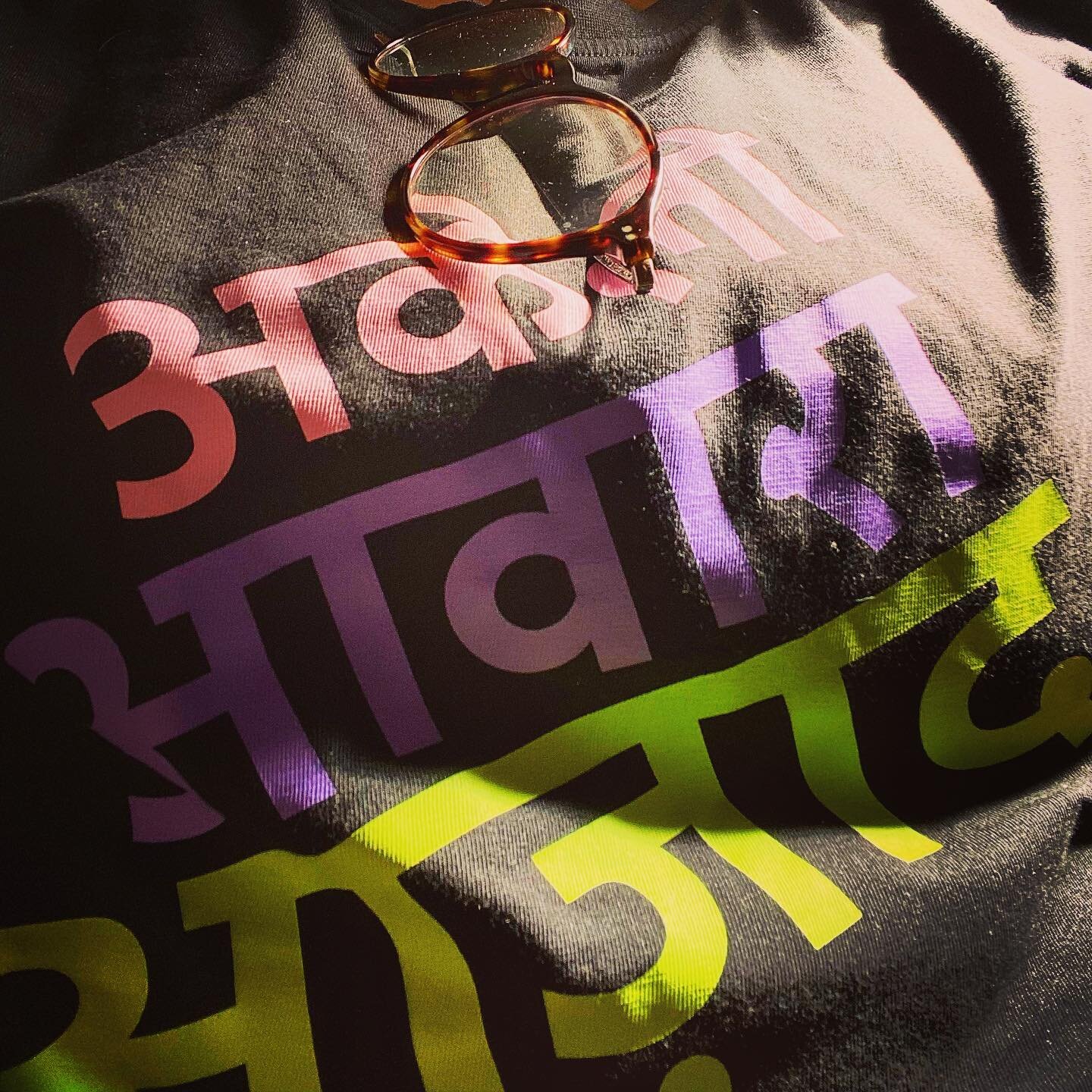

After a brief introduction of everyone present, the meeting proceeded with a brief discussion on eve teasing and the intervention that will take place. ‘Y ARE U LOOKING AT ME’ is an intervention where a group of women wears a giant letter made of red reflective tape on their shirts. They then stand idly on the streets or zebra cross, staring at the vehicles and passers-by without a word. Together, the letters on their shirts form the sentence ‘Y ARE U LOOKING AT ME’, demanding attention by asking a silent question. When the traffic light flashed to green, these women will disappear to the sidewalks. A group of male volunteers are already there, distributing pamphlets and engaging passers-by about in a conversation about what they just saw and relate it to eve teasing. The idea behind this intervention is an act a female gaze to reverse the male gaze that often times could be considered as a form of eve teasing. Because it is so unusual, onlookers often look away or feel embarrassed after an encounter with the female gaze. Despite being done without a word, the twist of gender dynamics in this intervention provoked the interest of people in the sidewalk and opened up the space for public dialogue – the aim Blank Noise strives to achieve.

Jasmeen told me that after this point some people started asking “But how will the public get what we’re talking about?” The idea of addressing an issue with such an ambiguous approach was indeed difficult to digest for some people – including me. The intervention did not explicitly mention eve teasing nor did it convey any clear message; there was no such thing as a placard that says “Stop Eve Teasing” or something similar. There was no specific proposal. The playful performance definitely is provocative enough to generate public dialogue, but what change will it create?

Blank Noise coordinators then encouraged people to experience the intervention first before making conclusions. The various roles are introduced and the volunteers were free to choose what they want to do. There are people who opted for the backstage work of preparing the red tapes and printing the pamphlets, some wanted to perform, while others are more contented to talk with the public afterwards. After the intervention took place, Jasmeen found that the feedback from the volunteers showed that the initial doubts disappeared.

Although there were people who did not want to talk to the volunteers, in general they were surprised by how open the public was to the conversations. “Maybe people are tired of the old ways of just meeting on the streets and trying to convince others through protests or petitions,” said Aarthi Ajit, a 25 year old research assistant who helped organize a Blank Noise Bangalore street intervention in 2008. “Maybe we need to look for different ways to get people’s attention and the creative, playful, and non-confrontative approach will work better than aggravation in making people think of the issue and become part of the movement.” She further explained that widening definitions of street sexual harassment and proposing tangible solutions are helpful to create the open attitude, while some people, especially men, could feel alienated by a poster that depicts men being violent to women as all men were labeled as perpetrators. This may be able to explain the public interaction as well as the numerous media coverage Blank Noise received for these street interventions. In this sense, people who doubted that the public would respond no longer questioned whether Blank Noise’s message would get through.

However, the question of whether the intervention made any change is still valid, considering that there is no means for Blank Noise to follow-up with the many people on the streets about whether they change their perception or behavior on street sexual harassment. Instead, the change could be detected within the volunteers.

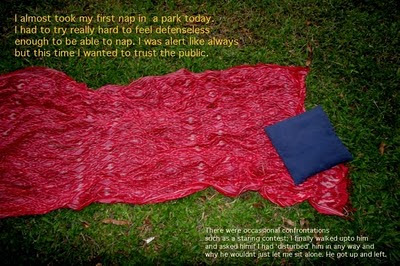

Hemangini Gupta, one of Blank Noise coordinators, recalled her first experience of performing the intervention. “It felt strange, but fun and empowering in a way. I never realized how disconnected I was from the streets before the intervention - I would never look at people before. It felt very safe knowing that I could just stand and look at people without any repercussions.”

Annie Zaidi, another Blank Noise coordinator, blogged about how her experience with Blank Noise interventions changed the way she deals with street sexual harassment. “Something has changed. This time, my reaction is different from what it would have been two years ago… I was surprised, felt contempt and anger – but I did not feel fear. This, I realize now, is because of Blank Noise, partly. .. It is as much about dealing with women’s fear of public spaces and strangers as it is about dealing with sexually abusive / intimidating strangers.”

Hemangini and Annie’s stories were echoed by many other volunteers. Jasmeen said that it was when Blank Noise started articulating that the change occurs internally first and blurring the line between the audience and the “Action Heroes”. The volunteers are as affected by the process as the viewers; they are mutually dependent on each other for the intervention experience to be meaningful. That is why Blank Noise does not think of “an audience”, everyone is a participant and co-creator in the experience.

Instead of shouting “Stop street sexual harassment!” or performing a street theatre with spoken words, Blank Noise chose to quietly ask “Why are you looking at me?” on the streets. They welcome many people, but the strength of its interventions does not lie in numbers. Blank Noise thinks about their issues differently and consequently, they also do things differently.

This is the fourth post in the Beyond the Digital series, a research project that aims to explore new insights to understand youth digital activism conducted by Maesy Angelina with Blank Noise under the Hivos-CIS Digital Natives Knowledge Programme.