BBC Report : Anti Rape Law India

#ParliamentWatch

Justice Verma Committee Report

Alchemizing Anger to Hope- Arvind Narrain in response to the report below

Against Castration

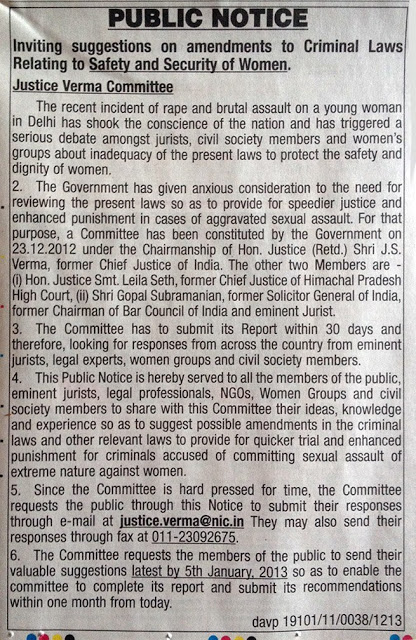

PUBLIC NOTICE : JUSTICE VERMA COMMITTEE

Sexual Assault laws

Broadly, rather than viewing ‘sexual assault' as a mechanical substitute for ‘rape' under Section 375 of the IPC, the effort of rights groups has been to think through the feasibility of formulating a chapter on sexual violence/atrocity that will define a range of such violence in a manner in which the focus shifts from the penetrative logic of definitions hitherto used to the assaultive nature sexual violence.

That article here.

To contextualise what's happening in India within the context of international debates, we've invited our first Guest Post! It's from Megan Hjelle who's been researching this issue for the Alternative Law Forum, Bangalore.

Gender-Neutral Sexual Assault Laws - A Brief Summary

Gender-Neutral Sexual Assault Laws - A Brief Summary Since the 1997 Writ Petition filed by Sakshi regarding amendments to India’s penal code regarding rape, gender neutrality has emerged as a lingering controversy. As currently written, India’s rape laws recognize the male/perpetrator - female/victim as the only framework within which rape can occur and regards penile-vaginal rape as the only “real” form of rape.

When the draft bill for amendments to the rape law was introduced with the intent of updating and expanding the laws into a spectrum of sexual assault offenses, few could have known that the topic would be such a lightning rod, pushing to the forefront fundamental contestations of the nature of gender itself. In an attempt to understand why the issue of gender-neutrality has been so uniquely contentious within the Indian context, the developments of gender-neutral sexual assault laws in other countries may provide some insight.

Rape law reform in countries such as the U.S., Canada, the U.K., Germany, and Australia produced, among other legislative developments, gender-neutral sexual assault laws. This note seeks to provide a brief summary of gender-neutral sexual assault laws along the following lines of inquiry:

- When did the shift to gender-neutrality occur?

- Why did the shift occur?

- What, if any, were the feminist stances in opposition and counter-responses?

- What impact, if any, have the application of gender-neutral laws had?

As most of the relevant data on the topic comes from research focused on the U.S., this summary will use the U.S. reform as its point of departure, with relevant comparisons to other nations with gender-neutral sexual assault laws as well.

Under the U.S. Model Penal Code, adopted by most U.S. states, rape was originally a crime that could only be perpetrated by a male on a female. The early Model Penal Code sex offenses were drafted under the influence of Kinsey’s research on sexuality. As well as creating a sexual offense hierarchy of severity, at the top of which was penile-vaginal rape, the drafters also required evidence of force in order to establish a rape. The drafters, fearing unfair prosecutions of defendants during a time when rape could still result in capital punishment, thought the evidence of force requirement would protect against false charges. Instead, it made successful rape convictions rare and re-victimized rape survivors by putting them on trial.

In the 1970’s, however, on the heels of the “Sexual Revolution,” the crime of “rape” was changed to “sexual assault” in an effort to de-emphasize the sexual elements of the crime and re-cast it as a crime of violence. The Michigan 1975 Criminal Sexual Conduct Statute served as a national model for implementing many of the rape law reforms that have now been adopted to some degree by most of the U.S. states. The reforms were largely a result of the feminist movement, which had as one of its fundamental objectives, the goal “to change peoples’ awareness and perceptions of violence against women.”

In comparison, Canadian rape law reform began in the early 1980’s and, in the U.K., sexual assault was not recognized as gender-neutral until 1994.

The development of gender-neutral sex offenses within the U.S. and elsewhere, is marked by a lack of direct discussion. This seems to be due to a confluence of factors relating to the goals of the feminist movement. At least one researcher has posited that “some extension of the coverage of rape laws was implicit in feminist objectives.” Feminists set out to “challenge the stereotyped assumptions about male roles and female sexuality” by “achiev[ing] comparability between the legal treatment of rape and other violent crimes, prohibit[ing] a wider range of coercive sexual conduct and expand[ing] the range of persons protected by law.”

Because feminists hoped to put an end to the phallocentricity of the laws as written and to emphasize the victim’s experience of violation, shifting the focus “from bodily harm to the protection of autonomy,” a gender-neutral law seems implied since, theoretically, it would capture more violative acts and would topple the hierarchy of penile-vaginal rape. Even at the time the Model Penal Code sex offenses were created, the drafters recognized the possibility that a gender-neutral approach “could also help to abrogate certain sex stereotypes that our society is appropriately beginning to address.”

Some researchers also identify as a factor changing social and sexual norms. For instance, one researchers posits that, social acceptance of oral and anal sex contributed to the shift toward gender-neutrality, while another attributes it to increased tolerance of more and difference types of sexual activity.

A researcher of Canada’s rape reform goes even further to identify gender-neutrality as merely a result of more primary reforms, rather than an end in itself.

Because, as suggested above, gender-neutrality may have seemed like a natural step in the feminist agenda rather than a focal point of the reform and as a result of practical reasons, the shift to gender-neutrality seems to have encountered little direct opposition in the U.S.

For instance, as previously mentioned, feminists had several linked objectives behind the reforms. Because of this, the rape law reforms were significant and numerous, with variations between states. So, states like Michigan made changes to remove the resistance requirement, remove immediate reporting requirements, shift the burden of proof, legitimize the victim’s testimony without corroboration, remove the marital exception, enact “Rape Shield” laws, provide an entire continuum of acts to be included under the term “sexual assault,” with gender-neutrality often being just one part of this array of reforms.

The single point of contention against gender-neutral sexual assault laws represented in the feminist literature seems to have developed retrospectively, rather than concurrently with the reform. And, in fact, that argument is best distilled and articulated by a recent argument in opposition of any gender-neutral amendments in Indian legislation:

There seems to be a presumption that if women can be framed as violators, then the trauma of rape for women as victims would be reduced and the stigma attached to the offence would peel off.

The response to this contention pivots between the arguments that gender-neutral terms do not preclude a gendered response to sexual assault, nor does it erase women’s experiences of sexual assault to include men. In also highlighting research indicating the trauma experienced by male victims of sexual assault, one researcher succinctly counters:

A principle of criminal law is, surely, that all persons should be protected equally from harm of like degree.... The case for treating crimes of like heinousness similarly appears to be stronger than that calling for a distinction to be made between penetration of the female body and penetration of the male body, whatever the sex of the actor.

Although some have tried to argue that gender-neutral laws have impeded the progress of rape law reform in combating sexual assault by introducing male victims, this argument does not seem corroborated by significant research. In fact, the majority of research shows that introducing gender-neutral laws and the rape law reform in general, have not had either a significantly positive or a significantly negative impact on sexual assault in the U.S. as of yet.

In conclusion, gender-neutral sexual assault laws were brought about during a period of intense legal reform initiated by feminists during the 1970’s to 1980’s in numerous nations and states as an attempt to trouble gender stereotypes and biases. There is an ongoing debate regarding the benefits and detriments of gender-neutrality to feminist goals, but research shows that the rape law reform has had little significant statistical impact on sexual assaults.

Megan is a second-year law Brooklyn Law student committed to providing advocacy and representation as a public interest lawyer. Her work is rooted in an interest in the ways globalization, migration and gender perpetuate and subvert each other. Megan has worked with the Coalition to Abolish Slavery and Trafficking in Los Angeles, where she helped match trafficking survivors with services and coordinated trainings to promote the identification and referral of trafficked individuals. More recently, Megan has worked at the Safe Horizon Anti-Trafficking Program. There, she developed and implemented a media outreach plan, helped maintain and strengthen international partnerships, coordinated trainings and worked on clients’ T-Visa and Asylum applications. Megan hopes to combine her background and legal education to facilitate a holistic, community-centered approach to advocacy for underserved populations and is currently pursuing these goals in an internship at the Alternative Law Forum in Bangalore.

What is important is that women are made aware of what their rights would be if the law is passed- Kalpana Sharma

The enhancement of the sentence of former Haryana DGP S.P.S. Rathore, charged with molesting 14-year-old Ruchika Talwar, from just six months to one and a half years, is a very small step in rectifying the glaring anomaly in the law that allowed him to almost get away with a serious crime. In the absence of the popular furore over what happened, and the determined efforts of the young woman's friends and family, it is possible that Rathore would have continued to hold office and escape the jail sentence awarded to him. But even as many will believe that 18 months is hardly adequate punishment for a crime that led to a young woman taking her own life, the sentencing is the beginning of an important process of change in our antiquated laws dealing with sexual assaults of all kinds.

Ruchika's is only one case. There are hundreds of such cases in India that never reach the point of conviction. And many more incidents that are never even reported. But because more such cases are coming out in the open, the demand for a change in the law has built up to the point that the government has finally taken note.

New Bill for Sexual Offence:

The proposed law makes it mandatory to end the trial of cases relating to sexual offences within a 6 month period.

The new law proposes:

Sexual abuse is defined to include not just physical but also mental harassment. Punishment for both to be similar.

Sexual abuse to be treated on par as rape, which means punishment for both to be equally stringent. Until now, maximum punishment for sexual abuse is one year.

Onus to prove that suicide was not due to sexual harassment lies with the accused.

All cases of sexual harassment to be dealt with special courts and cleared within 6 months to a year.

links:

toi,

dna

RUCHIKA

"I feel that Ruchika is still alive in every girl who is being molested, and violence against women. I request you to join us ... . I am launching a fight against molesters and against this system, also for fight for justice for my friend Ruchika" says Aradhana Parkash Gupta, who, as a teen, witness Ruchika being molested by a senior police officer in Haryana. Since then, Aradhana and her father have led a campaign to ensure that the policeman, SS Rathore, pays for assaulting a 14-year-old and then harassing her family, driving her to commit suicide.

more links:

http://www.indianexpress.com/news/Fresh-FIRs-filed--new-law-coming-on-sex-offences/561321

9/9/2010:

Rathore denied bail:

http://www.hindu.com/2010/01/09/stories/2010010957410100.htm

http://www.telegraphindia.com/1100109/jsp/nation/story_11963036.jsp

REPORT STREET HARASSMENT : TAKING LEGAL ACTION

video sourced from here

Eve teasing maybe perceived as a 'joke or a prank', but it is also recognized as a criminal offence. Aarti Mundkur, Alternative Law Forum, Bangalore, answers our questions on what one can do towards taking legal action when 'eve teased'.

1. All about FIRs and procedure to lodge one.

An FIR (FIRST INFORMATION REPORT) is the complaint that a person lodges at a police station, reporting the incident that is alleged to have occurred. It is the first information that the police receive regarding the commission of a Cognizable Offence, hence First Information Report.

An FIR can only be lodged at a police station. At every police station there is an officer designated as an SHO (Station House Officer) whose job it is to lodge FIRs. Usually, FIRs are lodged at the police station in whose jurisdiction (geographical area that comes under the purview of that police station) the offence has occurred.

It is preferable to lodge the FIR in the jurisdictional police station. If that is not possible, you will have state why, and the police will forward the the FIR to the concerned police station for investigation.

An FIR may be given in writing or orally. Your complaint in writing is reduced to the basic facts and put into a standard format of the FIR. You are entitled to read it make changes etc and also get a copy for yourself FREE OF COST. If you orally lodge a complaint, which the police officer writes down, please read it and make sure that it is accurate.

You have the right to lodge an FIR, irrespective of the circumstances that surround the particular incident. Clothes you are wearing or being out late cannot be reasons given to you for not lodging an FIR. In the event that the officer does not lodge your FIR, you can ask the Inspector of the police station to do so. If that fails, get in touch with the Circle Inspector. Finally, the office of the Commissioner of Police can also lodge an FIR and forward it to the concerned police station. So, in the event that the SHO refuses to lodge your FIR you can work your your way up the hierarchy, and ensure that it is.

It is not necessary that you should name the person you are accusing. It is very common to not know who the person is. If possible try and get a name or a good description. An FIR can be lodged against anyone, including public servants.

Procedure to lodge an FIR.

An FIR should have the following details-

1) a detailed description of the incident- date, time, place included.

2) If you know the accused- then his name and address. If not, as close a description as possible.

3) You must also put down exactly what happened. E.g. If you were felt up- how and where.

2. Do I have to report the incident only to another male officer?

there are all women's police stations that one can complain at. There is one close to the Corporation (Ph: 22290228/ 222 16242) However it is not mandatory for all police stations to have women officers.

3. How long does the whole procedure take? What am I getting involved in by lodging an FIR or reporting the 'eve teaser'?

Lodging of an FIR does not take very long, maybe a few hours, at the most. By lodging one, you are putting the criminal justice mechanism into motion That is, you are asking the police to begin investigating the incident that you have reported. It is then the job of the police to investigate, arrest, take down statements etc. You may be called by the police to identify the person/s they have arrested. The police then have to file what is called a chargesheet and then the case goes to trial before a judge, where you will be the primary witness, along with others, if there are any. It is difficult to say exactly how long this whole process takes. But one can safely say that it will be at least a few months- 4 or more, for the case to actually go to trail before a judge.

4. I think I was eve teased. This guy just looked at me in a way that made me feel sick. How can I take any action against it? I don't even know who he is. What constitutes as sexual harassment in the streets? What according to the law can be seen as 'eve teasing' or street sexual harassment? Is it looking, staring, and groping, stalking? What can police do to the perpetrator/ eve teaser? How is he punishable?

Section 354 of the IPC- requires that there be assault or criminal force used intending to outrage the modesty of a woman or knowing that it will outrage her modesty. A person found guilty can be imprisoned for a maximum period of 2 years, or with a fine, or both. So, under this section a 'look' may not be enough to constitute an offence. For more details look at Section 96 of the Karnataka Police Act.

Section 509 of the IPC is broader in its purview. It includes words, gestures, sounds or exhibition of objects with a view to insult the modesty of a woman. It also includes the words “intrudes upon the privacy of a woman”. The offence is punishable with a maximum imprisonment for one year, or a fine, or both.

In the case of both these provisions, it is difficult to say what exactly constitutes an offence. Courts have held that whistling, passing comments about a woman's body, singing songs etc, come under S.509. In any case, a 'look' that makes you uncomfortable may be very difficult to establish as an act that outrages your modesty.

Groping and stalking are definitely acts that come under the purview of both sections.

What is important is that neither section uses the explicit words eve teasing or sexual harassment. Although the latter is what the sections are trying to address. The focus is on the modesty of the woman.

6. Which police person can I complain to? Can I complain to the traffic police?

If you intend to initiate a criminal case you must lodge an FIR at the police station. The traffic police can assist you in reaching the police station or if they have witnessed the incident can be made witness. Sometimes it may be enough to create a scene by getting the traffic police involved and causing embarrassment to the man.

7. If I report him, how do I protect myself after that?

Its unlikely that you will need any kind of protection. Once he is arrested, he will have to get bail before he gets out of jail. You can ask the police for protection, if there are threats etc that are made. Bail may even be canceled if there are threats etc being made to the complainant.